Melbourne Tram Museum

- Follow Melbourne Tram Museum on Twitter

- Follow Melbourne Tram Museum on Facebook

- Follow Melbourne Tram Museum on Instagram

- Follow Melbourne Tram Museum on Pinterest

- Follow Melbourne Tram Museum on Tumblr

- Subscribe to Melbourne Tram Museum's RSS feed

- Email Melbourne Tram Museum

1934 – Big issues in Australian tramways

In March 1934, the fourth Australian & New Zealand Tramways Conference was held in Sydney. The proceedings of the conference make fascinating reading, just to see how attitudes have changed over the years.

For instance the whole issue of safety was treated in what seems to us a very cavalier fashion. There was an extended discussion on fitting of tail-lights and stop-lights to trams, but the general consensus was that motorists should be able to see tramcars, as they were well lit. Any drunk or irresponsible driver damn well got what they deserved if they ran into the back of a tram. The belief was that a manual system of tail/stop-lights would not be operated correctly by drivers, and that an automatic system would not be reliable enough to be effective. The delegates also felt that fitting of tail/stop-lights would be seen as an admission of liability with respect to accidents.

This attitude spread to the use of tram speed limit signs. Adelaide actually removed speed restriction signs from intersections as a result of a car accident, where it was claimed that the tram involved was travelling at the speed of 10 mph rather then the posted 6 mph when the accident occurred. The tramways wore the liability from the subsequent court case, so took this action to prevent future occurrences.

An extended discussion was held on the issue of windscreen wipers – many operators believing that they were not required (except Hobart, who had been looking for a solution for some time, for obvious reasons), but that it was adequate to drive with the windscreen in the open position, or that the driver could hand wipe the screen if it was required. There was some discussion on the fact that it was now law for all motor vehicles to have a minimum of a hand operated wiper. The attitude of not introducing safety devices for fear of admitting liability was also present in this discussion – which seems unbelievable with regard to today’s legislative climate. The finishing point was that there was some interest in fitting wipers, but it wasn’t seen as a priority.

Along the same line was the use of warning lights for trackwork excavations, as there were a large number of motor car accidents in these circumstances. Sydney had invested in floodlighting and electric warning lights, and dispensed with watchmen (which had also reduced theft of plant and materials), but Melbourne was insistent in remaining with the tried and true methods of having a watchman in these circumstances swinging his oil lamp.

One of the most interesting papers was one on shortcomings of contemporary tramcar design, which hadn’t substantially changed in the previous forty years. The major issues were the high weight of tramcars, particularly unsprung weight, particularly compared with the power to weight ration of trolley buses, and the inadequacy of braking systems. There was an interesting proposal that had some similarities with the PCC car design, which was happening concurrently with this conference. In fact, the work of the President’s Conference Committee was explicitly referenced in the discussion of the paper.

The major feature of the local proposal was use of high-speed trolley bus type motors mounted on the body in conjunction with drive shafts to axles, but utilising a worm drive. It was also proposed to use automotive type drum brakes, rather than the traditional style which we all know and love. The objective was to reduce noise in conjunction with increasing tramcar acceleration and braking capability, as well as to reduce damage to the track by reducing the unsprung weight. Also covered was the intention of the PCC design to use a truck mounted motor rather than a body mounted motor.

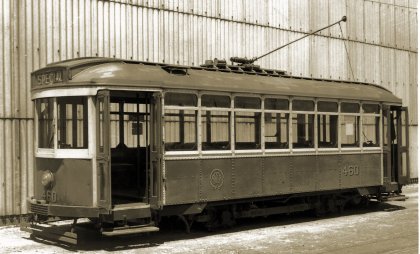

The discussion also revealed the reason why the M&MTB built two X1 tramcars (459 and 460) with worm drive – in order to reduce the unsprung weight. However, the experiment was a failure as there was no difference in ride quality for the extra complications and expense of construction. In addition, as those who have had Tri-ang 00 model locomotives can attest, the wheels of a worm drive tramcar will not rotate when being towed or propelled as a result of a breakdown, so tramcar failure will result in total blocking of service until the worm drive is disconnected.

M&MTB

X1 No 460 at Preston Workshops.

M&MTB

X1 No 460 at Preston Workshops. - Photograph from the Melbourne Tram Museum collection.

The other key item in this paper was the use of roller bearings, where it felt that the additional expense was not worth the advantages, as labour required for maintenance of standard bearings was cheap. How things have changed.

The general consensus (reading between the lines) was that this paper was too speculative, and that Australian operators could not afford to take risks but stick to what was tried and true – and let the Americans take the gamble on future tramcar design.

The big news with regard to tramcars was the order for 200 R class cars for Sydney then underway, and some admiration was expressed with regard to the magnitude of this commitment, together with the quality of an R class in which the delegates enjoyed a trip to Randwick Workshops. Also discussed were the W3 and W4 cars for Melbourne, with their all steel frame construction.

Other items in relation to tramcars included upholstered seating, together with a comparison of longitudinal and cross seating. On this last item, the operators preferred longitudinal seating due to the bigger crush loading capacity, but passengers everywhere preferred cross seating. And the buggers also wanted upholstery, but vandalism and seat slashing was a problem. Some things never change.

There was a comparison from Melbourne on use of trolley wheels, shoes and bow collectors – bow collectors were the most expensive, with the cost of shoes and wheels in Footscray being comparable (at one third of the cost of Fischer bow collectors), but wheels on the rest of the system being almost double the cost of those on the Footscray lines. The difference in cost was felt to be the lower speeds and lighter cars in Footscray. Lubrication was an issue, as the shoes had cast iron inserts rather than the graphite of today, lubrication being done by a device called a slicker, which was a trolley pole attachment that pressed a graphite stick against the wire.

The major issue with regard to use of shoes was the changeover required from round to grooved trolley wire, although they had major advantages in reduction in the number of types of fittings required. But everywhere lubrication and wear of trolley wheels on wire was an issue.

Of great historical interest were two articles on the Sydney tramways, one on the effect of the opening of the Sydney Harbour Bridge, the other on special workings such as racecourse and sporting traffic, which I will not atempt to summarise here.

There were a large number of papers on trackwork, rails and roadbed – but there was a common complaint from all operators on the demands of local authorities and motorists for upkeep of the road surface between the rails, when there was no liability for funding from this source – an early cry for the user pays principle. The lack of contribution from municipal authorities towards funding tramway shelters was also a problem. And there was a major issue on the imposition of sales tax on tramway authorities – particularly when it was not applicable to railway authorities.

An ominous note was struck by the great interest in compression ignition omnibuses (diesel buses to us modern folk), and the cost savings that could be enjoyed over both petrol-engined buses (fuel efficiency and power to weight ratio), and tramways (in the removal of infrastructure costs). But everyone recognised the superior carrying capacity of the tramcar over the omnibus, although they all realised the threat of the private motor vehicle towards all public transport.

But overall the conference proceedings are a fascinating overview of the issues faced by Australian and New Zealand tramway operators in the 1930s, and how they approached them. But one thing was clear – Australia and New Zealand operators were well up with what was happening in the rest of the world in all tramway related fields, so we were not a backwater.