Melbourne Tram Museum

- Follow Melbourne Tram Museum on Twitter

- Follow Melbourne Tram Museum on Facebook

- Follow Melbourne Tram Museum on Instagram

- Follow Melbourne Tram Museum on Pinterest

- Follow Melbourne Tram Museum on Tumblr

- Subscribe to Melbourne Tram Museum's RSS feed

- Email Melbourne Tram Museum

From rotary converters to solid-state: tramway substation architecture in Melbourne

The infrastructure required to supply electric power to Melbourne’s trams is usually overlooked by the travelling public, apart from the ever-present overhead wires. Few notice the anonymous windowless buildings along or near tram routes. These buildings are known as substations. If they did not fulfil their function, our trams would never turn a wheel.

Substation architecture reflects the design aesthetic chosen by the architect to express the brief given by his client, as well as the developments in electrical technology that have occurred since the first permanent electric tramways opened in suburban Melbourne in 1906.

The need for substations

Since the 1880s, electric trams have been powered by direct current (DC) at relatively low voltage – initially at 500 volts, but in later years more commonly between 600 and 750 volts. The technology involved in building relatively light DC motors suitable for trams was established by engineers like Siemens [1] and Sprague [2], fixing the basic design of tramcars by the end of the nineteenth century.

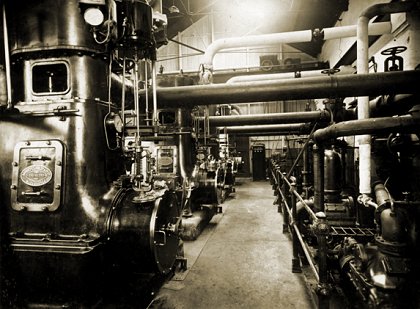

Interior of NMETL power house circa 1920, showing reciprocating steam

engines and steam pipework from adjoining boiler room.

Interior of NMETL power house circa 1920, showing reciprocating steam

engines and steam pipework from adjoining boiler room.- Photograph courtesy TMSV.

However, direct current has a major drawback. Over distance, transmission voltage drops quickly, so much so that tram performance falls off rapidly if the tram is much further than four kilometres away from the source of its power. Power transmission research led to the discovery that transmission of electricity as three phase high voltage alternating current (AC) resulted in much reduced power loss over distance. Additionally, high voltage transmission did not require the same thickness of conductors, reducing the amount of copper to transmit electricity. These two findings led to the abandonment of low voltage DC current as a method of power transmission, except in special cases. Electricity transmission by high voltage AC became the norm.

However, DC motor design was particularly suited to tramway traction, as the compact and light motors could easily be incorporated into the restricted space of contemporary tramway trucks and bogies. Additionally, safety clearances for overhead wires could be smaller with lower voltage DC traction current, leading to substantial cost savings in construction.

These factors would lead tramways to standardise on the use of low voltage high amperage DC current as the method of electricity supply to tramcars, necessitating the construction of electrical substations to transform high voltage transmission AC power down to low voltage DC traction power. This required the development of a method of voltage reduction and rectification of AC current to DC current, hence the need for substations to house the necessary equipment.

Early days

When the North Melbourne Electric Tramways and Lighting Company (NMETL) started operation in 1906, electricity generation and distribution in Melbourne was in its infancy. There was no widespread electricity network, or spare generating capacity to run a tramway. Therefore, the operator had little option but to generate its own power.

In order to minimise voltage drop at the outer end of its lines, NMETL built a power house at its tram depot, located close to the junction of its two routes from Flemington Bridge to Keilor Road and Saltwater River. Electricity was generated by three [3] coal-fired reciprocating steam engines [4], for consumption by both retail customers and the tramway itself.

The power house, now long since disappeared, was a typical example of early twentieth century industrial architecture. Massively constructed of brick, it made a profound statement of the solidity and permanence of the owning company, whose name appeared on a moulded fascia just below the roofline. Internally, the building was divided into three key spaces – the boiler room, the generating house and the electrical control room. The power house and other depot buildings were designed by the Melbourne firm of Ussher & Kemp, notable for their pioneering of the early twentieth century architecture style known as Federation or Melbourne Domestic Queen Anne. Further decorative elements were added to the building at some time after the photograph below was taken.

NMETL power house, Mt Alexander Road, Ascot Vale, pre World War I.

NMETL power house, Mt Alexander Road, Ascot Vale, pre World War I.- Photograph courtesy TMSV.

Vibration from the reciprocating masses of the steam engines together with the high speed rotation of the generating units and rotary converters required deep foundations to prevent damage to the building fabric. This would be a characteristic of tramway substations built over the next two decades, for as long as rotary converters were used for rectification of electrical current from AC to DC.

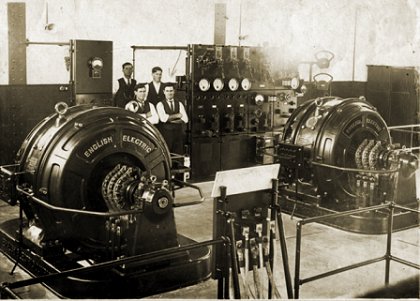

Interior of Ascot Vale substation

circa 1925, showing two English Electric rotary converters, the control

panel and a group of four substation attendants.

Interior of Ascot Vale substation

circa 1925, showing two English Electric rotary converters, the control

panel and a group of four substation attendants.- Photograph courtesy TMSV.

Other aspects of first generation tramway substation design are large doorways and high rooflines, necessary to permit easy handling of the electrical plant.

Growth of electricity generating and distribution companies in Melbourne removed the need for the new municipal tramway trusts [5] to operate their own generating plant. These organisations, located in the then outer suburbs of Melbourne, all built electrical substations in their depots. These consisted of rotary converters for current rectification, and in some cases supplemented with large banks of lead-acid batteries to meet spikes in power demand.

The largest and most ambitious of the new operators – the Prahran & Malvern Tramways Trust (PMTT) – embarked on a large program of tramway construction in the south-eastern suburbs of Melbourne. Its 1913 extension to Elsternwick led to the building of the first free-standing tramway substation in Melbourne, in Rusden Street Elsternwick – a small distance away from the tracks in Glenhuntly Road that it served.

Ex-PMTT

substation, Rusden Street, Elsternwick, July 2012. Now used for a

medical practice.

Ex-PMTT

substation, Rusden Street, Elsternwick, July 2012. Now used for a

medical practice. - Photograph courtesy Noelle Jones.

Located in a residential area, the substation was sympathetically designed to blend with the surrounding Edwardian housing stock. The red brick and stucco building was constructed with two glazed roof lanterns and parapeted walls with extended piers and horizontal and curved bays. It was commissioned in December 1914 with two 100kW rotary converters relocated from Coldblo Road Malvern, an automatic reversible booster and batteries for overload operation. Ownership of the building was boldly announced by a cast cement moulding on the central parapet.

The Rusden Street substation no longer fulfils a tramway purpose, as it was decommissioned in 1966. It survives in private hands, and has been listed on the Victorian Heritage Register due to its importance to the operation of Melbourne's early electric tramways.

Fitzroy

(Young Street) substation, surrounded by the buildings of the Australian

Catholic University, July 2012. Still in active use as a tramway substation.

Fitzroy

(Young Street) substation, surrounded by the buildings of the Australian

Catholic University, July 2012. Still in active use as a tramway substation.

- Photograph courtesy Noelle Jones.

Art Deco – a model for growth

Expansion of Melbourne’s electric tramway system paused between 1916 and 1923, due to a combination of the First World War and delays caused by the merger of the tramway trusts to form the Melbourne & Metropolitan Tramways Board (M&MTB). Construction of new substations did not proceed until the M&MTB formulated its 1923 General Scheme for the conversion of the cable tramway system and expansion of the electric tram network.

Camberwell

substation, July 2012. Note the extensive use of windows to provide

natural light to the interior. Still in use today.

Camberwell

substation, July 2012. Note the extensive use of windows to provide

natural light to the interior. Still in use today.- Photograph courtesy Russell Jones.

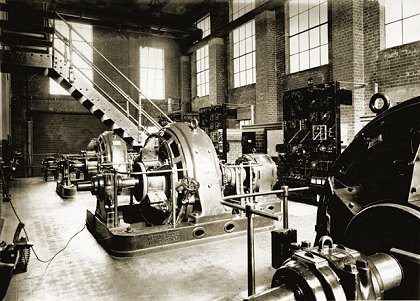

The M&MTB architect, Alan G. Monsborough, designed a series of large substations with common Art Deco elements. These were constructed between 1924 and 1929 in Camberwell, South Yarra, Ascot Vale, South Melbourne, Malvern Depot, Fitzroy (Young Street) and Carlton. All seven were designed to house rotary converters. Despite this technology now being long obsolete, their prime locations have meant that all but Malvern Depot, South Yarra and Ascot Vale continue to fulfil their original function, with modern solid-state rectification equipment replacing the original rotary converters. A late 1960s addition to the largest of these substations, Carlton, contains the central power control room for Melbourne’s tram network. Regrettably, this extension was not executed in the same style or materials as the original building. While the buildings at South Yarra and Ascot Vale remain, the substation equipment is now housed in a small structure at the rear of both properties.

Carlton

substation in Bouverie Street, July 2012. The brick building at the

rear of the main hall houses the main control centre for the electricity

supply to Melbourne’s tram system.

Carlton

substation in Bouverie Street, July 2012. The brick building at the

rear of the main hall houses the main control centre for the electricity

supply to Melbourne’s tram system. - Photograph courtesy Brian Louey-Gung.

All seven substations were constructed from red brick with differing degrees of cement rendering and decorative features. None were built to the same plans or floor layout, but show a continuity of design that extends through to the contemporary tram depots at Camberwell, Glenhuntly and South Melbourne [6]. All substations are notable for their use of windows in the upper storey, ensuring that the interior is well-lit with natural light. Essentially, the M&MTB was making a powerful statement regarding its brand through construction of these large buildings, emphasising its modernity and strength through use of the new Art Deco paradigm.

Ascot Vale substation, July 2012. Heavily coated with graffiti, this

building has been supplanted by a small modern substation at its rear.

Ascot Vale substation, July 2012. Heavily coated with graffiti, this

building has been supplanted by a small modern substation at its rear.

- Photograph courtesy Noelle Jones.

While these large substations were appropriate for their central locations in the tramway network, construction of such large buildings in more outlying areas could not be justified financially, where there was not the need for such elaborate and redundant substation equipment. This required a smaller and less ambitious design, particularly as these sites were primarily located in residential areas.

South

Melbourne substation, July 2012. Many mouldings typical of the 1920s

have been used for decoration around doors and other features.

South

Melbourne substation, July 2012. Many mouldings typical of the 1920s

have been used for decoration around doors and other features. - Photograph courtesy Russell Jones.

Over the same period four smaller substations were built to address this need, in Deepdene, Holden Street (North Fitzroy), Preston Workshops [7] and West Brunswick. As constructed, all expressed varying degrees of Moderne influence, particularly in details of decorative brickwork. This differed from the larger substations, which eschewed Moderne for a less confronting Greek Revival style.

Preston

Workshops substation, July 2012. The small annex at left with the

circular fan housing was added post World War II to house additional

substation equipment. This building has been supplanted by a modern

building elsewhere in the workshops.

Preston

Workshops substation, July 2012. The small annex at left with the

circular fan housing was added post World War II to house additional

substation equipment. This building has been supplanted by a modern

building elsewhere in the workshops. - Photograph courtesy Russell Jones.

The most radical of these buildings was constructed in West Brunswick in 1925-26, to serve the outer section of the new West Coburg line. Attractively built in red brick with a flat roof, it exemplifies early Moderne symmetrical design as applied to a small industrial building. The dominating feature is a central gated opening displaying the high voltage transformer – a perfect expression of the spirit of new technology inherent in Futurism. Attractive use is also made of decorative brick streamlining in classic Moderne horizontal and vertical elements, while sparing use is made of decorative bosses in cream brick.

West Brunswick substation, July 2012. Note the prominence given to

display of the high voltage transformer as a key decorative element

of the building.

West Brunswick substation, July 2012. Note the prominence given to

display of the high voltage transformer as a key decorative element

of the building. - Photograph courtesy Russell Jones.

The remaining three small 1920s substations were all built to a simpler, more traditional pattern. While they made restrained use of Moderne decorative brickwork to differing degrees, all three had pitched roofs.

Deepdene

substation, July 2012. A key feature of this building is the decorative

brickwork elements used on the corners of the building as well as

at the peak of the false arch above the door.

Deepdene

substation, July 2012. A key feature of this building is the decorative

brickwork elements used on the corners of the building as well as

at the peak of the false arch above the door. - Photograph courtesy Russell Jones.

Originally constructed in 1925-26, the Holden Street building was modified in 1936 with a new facade as part of the upgrading of substation capacity for the conversion of the North Fitzroy cable tram line to electric traction. The new facade was austere in nature, reflecting the trend in later Moderne styling to avoid unnecessary decoration. The only adornment applied to the building in its redevelopment was the application to the facade of “M&MTB” in raised white letters in an attractive Art Deco-styled sans serif font.

Holden

Street (North Fitzroy) substation, July 2012. The facade shows an

early use of cream brick, which was to become widely used across Melbourne

after World War II.

Holden

Street (North Fitzroy) substation, July 2012. The facade shows an

early use of cream brick, which was to become widely used across Melbourne

after World War II. - Photograph courtesy Russell Jones.

A significant advance in DC rectification made the construction of these smaller substations possible without the need for the massive foundations required by rotary converters. This was the introduction of mercury arc glass bulb rectifiers, which essentially could rectify AC current to DC current with no moving parts other than a cooling fan.

While the Holden Street substation remains in use, albeit with modern solid-state equipment replacing the original equipment, Deepdene and Preston Workshops substations have been replaced by new construction.

Austerity measures

The 1929 Great Depression had imbued the M&MTB with a more cautious financial approach than had existed in its first decade. It was less inclined to construct new facilities, instead adapting old buildings to new purpose in order to reduce costs. When the Brunswick cable tram route along Sydney Road was converted to electric traction in 1936, part of the now-redundant Brunswick engine house was used to house the substation for the route. This was made feasible through the use of mercury arc rectifiers, which did not require the deep foundations of rotary converters. The part of the 1887 building not required for the substation was leased to private interests.

Section of converted

Brunswick cable engine house used as substation, July 2012. The majority

of this 1887 building has been leased to a commercial business.

Section of converted

Brunswick cable engine house used as substation, July 2012. The majority

of this 1887 building has been leased to a commercial business. - Photograph courtesy Russell Jones.

The Second World War did not halt expansion of the Melbourne tram system. However, the only route extensions made were built specifically to service wartime industry, and were funded by the Commonwealth. This work required the construction of two new substations in 1942 and 1943, in Maribyrnong and Essendon respectively.

One factor in the design of these new buildings was determined by the introduction of centralised remote control for the entire tramway substation network by 1942. This meant that it was no longer necessary to have staff on site to operate the electrical equipment, so consideration of human habitability was no longer high on the list of requirements. The most visible consequence of this change was the absence of windows in both new buildings.

The architecture of the Essendon substation can be characterised as typical of wartime austerity. Constructed simply from red brick, it bears no ornamentation whatsoever, pretending to be nothing other than a substation – a function that it still fulfils.

Essendon substation, July 2012. Notable as the first Melbourne tramway

substation built without any ornamentation.

Essendon substation, July 2012. Notable as the first Melbourne tramway

substation built without any ornamentation. - Photograph courtesy Russell Jones.

The substation in Maribyrnong is much more interesting from an architectural perspective. Constructed in the midst of munitions factories during the darkest days of the Second World War, it was thought to be a likely air raid target. Therefore, it was built at the bottom of an abandoned quarry from reinforced concrete to protect it from blast effects. However, this was not thought to be sufficient protection. It was also covered with an irregularly-shaped flat concrete roof that did not betray any straight lines. Even the cast concrete walls separating the external transformer bays lacked any sense of a straight edge.

Thus from the air, the substation appears to be nothing more than a pool of water at the bottom of the quarry. Clearly, the high value of the electrical equipment it contained along with the difficulty of replacing it in the event of damage from aerial bombing justified this degree of camouflage. Even today, the Maribyrnong tramway substation is difficult to see, its location and design features ensuring that it is almost invisible to the public. This obscure structure is one of the few tangible reminders outside a museum of a time when the continuing existence of Australia as a nation was under threat.

Maribyrnong substation, 2013. The irregular shapes of the roof and

walls are clearly evident, the removal of straight lines in the building

designed to camouflage the building from both overhead and oblique

aerial observation.

Maribyrnong substation, 2013. The irregular shapes of the roof and

walls are clearly evident, the removal of straight lines in the building

designed to camouflage the building from both overhead and oblique

aerial observation. - Photograph courtesy Kerry Jordan.

Postwar renewal

Between 1953 and 1956 a series of three handsome substations were built in East Kew, Clifton Hill, and Northcote. These were an essential part of the postwar plans of the M&MTB to continue expansion of the tramways network. All three were built in cream brick to house large steel-tank mercury arc rectifiers, rather than the banks of small glass bulbs previously used.

Northcote substation, July 2012.

The heavy feeder cables entering the building show it is still in

use as a tramway substation.

Northcote substation, July 2012.

The heavy feeder cables entering the building show it is still in

use as a tramway substation. - Photograph courtesy Noelle Jones.

Steel tank rectifiers had the advantage of handling much more current than the fragile glass bulbs they were superseding. However, this came at a price. Heat dissipation was a problem, particularly in Melbourne’s hot summers. A prominent characteristic of all three substations were the large circular vent covers protecting air circulation fans.

Clifton Hill substation, July 2012. One of a trio built in cream brick

after World War II, the most prominent feature being the circular

vent covers housing cooling fans.

Clifton Hill substation, July 2012. One of a trio built in cream brick

after World War II, the most prominent feature being the circular

vent covers housing cooling fans. - Photograph courtesy Noelle Jones.

A fourth contemporary substation was built in Fitzroy to a similar design, the only significant difference being the substitution of red brick for the cream of the other three. This was more in keeping with the surrounding Edwardian housing stock.

East Kew substation was built with two steel-tank rectifiers, but one of them was never commissioned. It was intended to power the never-built Burke Road tram extension from Cotham Road and across the Yarra River to Heidelberg. This extension had been planned since 1923, when the Burke Road bridge across the river was built with tram tracks already in place. Unfortunately, the ascension of the Bolte State Government in 1955 meant the end of the expansion of the tram network for over twenty years, and the land adjacent to East Kew substation, which had been intended for a large tram depot, was transferred to the Education Department to become Kew High School.

East Kew substation, July 2012. This building shows design elements

common with much of 1950s Melbourne housing stock, such as the use

of glass louvre windows for ventilation, and the dark glazed brick

used up to floor level.

East Kew substation, July 2012. This building shows design elements

common with much of 1950s Melbourne housing stock, such as the use

of glass louvre windows for ventilation, and the dark glazed brick

used up to floor level. - Photograph courtesy Russell Jones.

This was not the end of substation development, as the new technology of silicon solid-state diode rectifiers offered substantial benefits over the old technology, both in terms of operating costs and reliability. Two new substations were constructed in unobtrusive grey brick in St Kilda and Elsternwick in 1966 and 1967 respectively. As architectural statements, they had more in common with the wartime Essendon substation than anything that had gone before. These austere buildings cannot be mistaken for anything other than utility buildings, as all decoration became subservient to function.

St Kilda substation, July 2012. The utilitarian character of this

building including its construction from grey concrete brick is typical

of many Melbourne government buildings and churches of the late 1960s.

.

St Kilda substation, July 2012. The utilitarian character of this

building including its construction from grey concrete brick is typical

of many Melbourne government buildings and churches of the late 1960s.

. - Photograph courtesy Noelle Jones.

Elsternwick substation, July 2012. This building is almost a carbon

copy of the St Kilda substation, but uses a different brick.

Elsternwick substation, July 2012. This building is almost a carbon

copy of the St Kilda substation, but uses a different brick. - Photograph courtesy Noelle Jones.

The substation built for the East Burwood extension to Middleborough Road in 1978 continued in the same theme, replacing the grey brick with a brown brick more in keeping with its location in the middle suburb of Burwood.

Burwood substation, July 2012. Although built a decade later than

the St Kilda and Elsternwick substations, this building uses similar

design features.

Burwood substation, July 2012. Although built a decade later than

the St Kilda and Elsternwick substations, this building uses similar

design features.- Photograph courtesy Russell Jones.

Within the Central Business District, the 1975 Crombie Lane substation continued in the functionalist theme. It also demonstrates an unconscious connection to the camouflaged wartime building in Maribyrnong. The building itself is largely underground, the essential boxiness of the structure being more or less invisible to the casual observer. The end result is an effective camouflaging of the building’s function.

Crombie Lane substation, July 2012. This is the only part of the substation

building that is visible above ground.

Crombie Lane substation, July 2012. This is the only part of the substation

building that is visible above ground. - Photograph courtesy Noelle Jones.

The advance of technology meant that prominent permanent substation buildings were becoming a thing of the past. Effective substation units could be constructed in cheap, demountable buildings, reducing both construction time and cost. These utilitarian structures were used for both new installations and replacing many of the obsolete substations, often being placed unobtrusively behind the old building. The East Burwood substation built for the extension of route 75 to Blackburn Road is a typical example, although it is a new installation. The only concession to aesthetics was the brick-patterned cladding applied to the exterior.

East Burwood substation, July 2012. This demountable building is clad

in faux brick sheeting.

East Burwood substation, July 2012. This demountable building is clad

in faux brick sheeting. - Photograph courtesy Russell Jones.

Vanished substations

The Richmond cable engine house was another example of a conversion to a substation, but unlike Brunswick it has not survived to the current day. The 1885 building was demolished in 1991 for the widening of the Bridge Road/Hoddle Street intersection, and the substation at the rear replaced by a demountable building similar to the East Burwood example, but clad in pebblecrete rather than brick-patterned sheeting.

Former Richmond cable engine house circa 1980. Prior to demolition

in 1991, the tramway substation was housed at the rear of the building.

Former Richmond cable engine house circa 1980. Prior to demolition

in 1991, the tramway substation was housed at the rear of the building.

- Photograph courtesy City of Yarra Library.

Other substation buildings built by the M&MTB have also vanished. An eighth Greek Revival substation was built in the 1920s by the M&MTB, although it was smaller than the other examples. Located in Nelson Street St Kilda, it was demolished in 1967 to make way for the redevelopment of the St Kilda Junction intersection and Queens Road underpass.

Demolition of a row of houses has exposed the rear of the old St Kilda

substation, not long before it too was demolished in 1967.

Demolition of a row of houses has exposed the rear of the old St Kilda

substation, not long before it too was demolished in 1967. - Photograph from the Peter W Duckett Collection.

The M&MTB and its predecessors were not the only builders of tramway substations in Melbourne. As part of the upgrading of its St Kilda to Brighton Beach tramway, Victorian Railways (VR) constructed a series of four-motored bogie tramcars from 1917, requiring the upgrading of the electric supply. The steam-powered generating plant at the Elwood Depot was replaced by a high voltage connection from the Newport Powerhouse, the latter being constructed for the electrification of the Melbourne suburban railways. This required a new substation, built in the rear of the Elwood Depot grounds shortly after World War I.

VR tramway substation at rear of Elwood Depot, date unknown. It is

decidedly less ornate than the contemporary M&MTB Greek Revival substations.

VR tramway substation at rear of Elwood Depot, date unknown. It is

decidedly less ornate than the contemporary M&MTB Greek Revival substations.

- Photograph from the Lloyd Rogers collection.

Built in red brick, the Elwood substation showed stylistic similarity with contemporary railway substations built by VR, although it was smaller and simpler in design. The cement mouldings above the ground floor windows are an early example of decorative features that would become common on Art Deco buildings. The large windows flooded the spacious interior with natural light, characteristic of other VR substations. Unfortunately the Elwood substation did not long survive the closure of the VR tramway in 1959. It was demolished shortly thereafter, the former site now occupied by a small housing estate.

Interior of Elwood substation, the natural light showing the Westinghouse

rotary converters and other electrical equipment to advantage. Date

unknown.

Interior of Elwood substation, the natural light showing the Westinghouse

rotary converters and other electrical equipment to advantage. Date

unknown.- Photograph from the Lloyd Rogers collection.

A rare survivor

Malvern Depot substation was designed by Alan G. Monsborough, the Chief Architect of the Melbourne & Metropolitan Tramways Board (M&MTB). Constructed in 1929 as part of the expansion of Malvern Tram Depot, it is finished in a stripped Greek Revival style consistent with most of Monsborough’s larger buildings for the M&MTB. As such, it is the most recent member of a group of substations built in the same style over the period 1924 to 1929 to cater for the expansion of the Melbourne electric tramway network.

When considering these substations as a series, the progression of their design is clear, as extraneous decoration and complexity are progressively eliminated in each subsequent building, until it is reduced in this example to the bare essentials of stripped Greek Revival, which probably best represents the final evolution of Monsborough’s work in this style as applied to electrical substations. Use of this style across not only substations but also other major M&MTB buildings such as tram depots and the Preston Tramway Workshops was a deliberate expression of corporate identity, underlying the modernity of the new tramways organisation, as well as its contribution to the civic life of Melbourne.

The key decorative elements in the building are the two faux brick columns in relief, with capitals and bases finished in cement render, referencing Monsborough’s use of columns in other contemporary M&MTB buildings, notably the traffic offices at Camberwell Depot and the administration building at Preston Workshops. Additional use of cement render is used to highlight the frame and lintel of the large entrance door and the fascia/frieze.

Malvern depot substation, 2014, adjacent to Tram Shed 1 in Coldblo

Road.

Malvern depot substation, 2014, adjacent to Tram Shed 1 in Coldblo

Road. - Photograph courtesy Miles Pierce.

The substation building is interesting due to its location in Coldblo Road next to the original Malvern Tram Depot built in Anglo-Norman Revival style two decades earlier, especially given their closely related functions. The depot was designed by Leonard Flannagan, Melbourne’s other notable architect of tramway buildings in the early twentieth century. The juxtaposition of the two buildings – the only location in which work of the two architects may be viewed side by side – allows the observer to easily contrast the plethora of small design features popular in the Edwardian period as opposed to the simplicity of the classical features inherent in stripped Greek Revival as expressed two decades later.

It should be noted that the design of the substation is consistent in style with the design of tram shed number two on the opposite side of Coldblo Road, built in the same year as part of the expansion of the facilities at Malvern Depot.

Although it has not been in use for some years, Malvern Depot substation is notable for the completeness of the original electrical equipment installation, including the original English Electric rotary convertors. This makes it a unique survivor of this formerly common type of first generation electrical equipment which was essential for the operation of DC electric tramways and railways in the first three decades of the twentieth century.

Invisible buildings

The small size of modern substation equipment has led to the advent of the “invisible” substation, particularly on high value city sites. In this case, the substation becomes a tenant in a larger building, usually an office tower. The only external indication of the presence of a tramway substation is a door in a blank wall bearing a warning message, or possibly a parking sign restricting vehicles from blocking off access. Both the Kingsway and Docklands substations are representative examples of this initiative.

Kingsway substation, July 2012. Only the signs on the door, and the

large ventilation grille above the door on the right provide any indications

as to its use.

Kingsway substation, July 2012. Only the signs on the door, and the

large ventilation grille above the door on the right provide any indications

as to its use. - Photograph courtesy Russell Jones.

Docklands substation, August 2014. The door leads to the substation.

Docklands substation, August 2014. The door leads to the substation.- Photograph courtesy Russell Jones.

This trend has not meant the disappearance of the purpose-built substation. Recent years have seen the construction of smaller buildings built in austere tilt-slab form, although the new Malvern substation is significantly larger – a twenty-first century analogue of the large 1920s Art Deco substations. However, this building does not proclaim its function, unlike its predecessors. Instead, it looks like nothing other than an apartment building, albeit with fewer windows than might be considered usual.

Malvern substation, July 2012. This building presents to the casual

observer as nothing other than an undistinguished block of flats.

Malvern substation, July 2012. This building presents to the casual

observer as nothing other than an undistinguished block of flats.

- Photograph courtesy Noelle Jones.

The disappearance of highly visible branding on substation buildings can be attributed to a combination of a number of factors, including security concerns and cost reduction. Regrettably, buildings associated with Melbourne’s electric trams are no longer a source of civic pride, but instead are a target for vandals and graffitists.

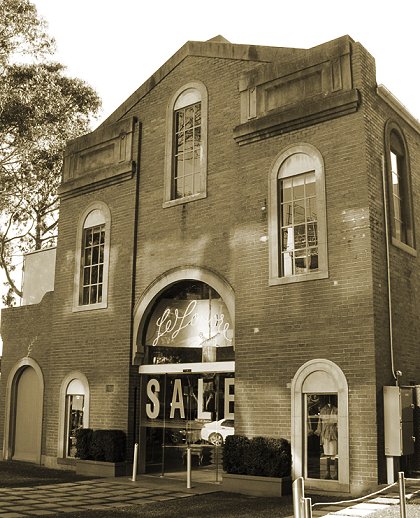

Many of the older substations are now derelict, having been superseded by newer structures. This has left otherwise noteworthy buildings without a purpose, destined to gradually fall into decay, despite many of them being placed on the Historic Buildings Register. But one of the former substations has found an innovative new use. The South Yarra substation in Daly Street has been attractively redeveloped as an exclusive clothing store. Hopefully, this example will see renewal of other substation buildings that have fallen into disuse.

The ex-South

Yarra substation in Daly Street, converted to an upmarket clothing

boutique. A small modern substation is located behind this building.

The ex-South

Yarra substation in Daly Street, converted to an upmarket clothing

boutique. A small modern substation is located behind this building.

- Photograph courtesy Noelle Jones.

Bibliography

Jones, R. (2003) Fares please! An

economic history of the Melbourne & Metropolitan Tramways Board,

Friends of Hawthorn Tram Depot

Keating, J. D. (1970) Mind the Curve! Melbourne University Press

Keenan, David R. (1985) Melbourne Tramways, Transit Press

M&MTB (1942) Annual Report

M&MTB (1966) Annual Report

Victorian Heritage Database (2012) 196A

Dawson Street Brunswick, retrieved 19 July 2012

Victorian Heritage Database (2012) 6-8

Rusden Street Elsternwick, retrieved 19 July 2012

Wong, M. (2012) Tramway

Traction Substations, Wongm’s Rail Gallery

Footnotes

[1] Ernst Werner von Siemens was a German engineer who built the first electric railway locomotive for display in the Berlin trade fair of 1879. The company he founded, Siemens & Halske, is still involved in the production of electric locomotives to this day.

[2] Frank Sprague was an American engineer who designed and constructed the first practical electric tramway using overhead wires in 1887, in Richmond, Virginia. He was responsible for many advances in electrical engineering, beyond the success of his first tramway.

[3] A fourth engine was added some years later to meet growing retail customer demand.

[4] The use of reciprocating steam engines for electricity generation was shortly to be made obsolete by the widespread introduction of more efficient steam turbines – the first major installation of which was for the tramways in Newcastle in the United Kingdom in 1904.

[5] The Melbourne-based municipal tramways trusts were:

- Prahran & Malvern Tramways Trust, opening in 1910

- Hawthorn Tramways Trust, opening in 1916

- Melbourne, Brunswick and Coburg Tramways Trust, opening in 1916

- Fitzroy, Northcote & Preston Tramways Trust, opened by the Melbourne & Metropolitan Tramways Board in 1920

- Footscray Tramways Trust, opened by the Melbourne & Metropolitan Tramways Board in 1921.

All were merged into the Melbourne & Metropolitan Tramways Board in 1920.

[6] South Melbourne tram depot was demolished in the mid 1990s. The site is now occupied by a large office building and a car dealership, while the depot function it fulfilled is now supplied by Southbank depot adjacent to the Port Melbourne light rail line. The former South Melbourne depot site maintains a link with the tramways, as one of the tenants of the office building is a Yarra Trams electrical substation.

Both Glenhuntly and Camberwell tram depots continue in their original function.

[7] The former substation at Preston Workshops was demolished in August 2014 shortly after first publication of this article, as part of the redevelopment of Preston Workshops into a ‘super depot’ for Yarra Trams.